Eating Disorders

It’s only human to wish you looked different or could fix something about yourself. But when a preoccupation with being thin takes over your eating habits, thoughts, and life, it’s a sign of an eating disorder. When you have anorexia, the desire to lose weight becomes more important than anything else. You may even lose the ability to see yourself as you truly are.

It’s only human to wish you looked different or could fix something about yourself. But when a preoccupation with being thin takes over your eating habits, thoughts, and life, it’s a sign of an eating disorder. When you have anorexia, the desire to lose weight becomes more important than anything else. You may even lose the ability to see yourself as you truly are.

Anorexia is a serious eating disorder. It can damage your health and even threaten your life. But you’re not alone. There’s help available when you’re ready to make a change. You deserve to be happy. Treatment will help you feel better and learn to value yourself.

What is anorexia nervosa?

- refusal to maintain a healthy body weight

- an intense fear of gaining weight

- a distorted body image

Because of your dread of becoming fat or disgusted with how your body looks, eating and mealtimes may be very stressful. And yet, what you can and can’t eat is practically all you can think about.

Thoughts about dieting, food, and your body may take up most of your day—leaving little time for friends, family, and other activities you used to enjoy. Life becomes a relentless pursuit of thinness and going to extremes to lose weight.

But no matter how skinny you become, it’s never enough.

While people with anorexia often deny having a problem, the truth is that anorexia is a serious and potentially deadly eating disorder. Fortunately, recovery is possible. With proper treatment and support, you or someone you care about can break anorexia’s self-destructive pattern and regain health and self-confidence.

Types of anorexia nervosa

There are two types of anorexia. In the restricting type of anorexia, weight loss is achieved by restricting calories (following drastic diets, fasting, and exercising to excess). In the purging type of anorexia, weight loss is achieved by vomiting or using laxatives and diuretics.

Are you anorexic?

- Do you feel fat even though people tell you you’re not?

- Are you terrified of gaining weight?

- Do you lie about how much you eat or hide your eating habits from others?

- Are your friends or family concerned about your weight loss, eating habits, or appearance?

- Do you diet, compulsively exercise, or purge when you’re feeling overwhelmed or bad about yourself?

- Do you feel powerful or in control when you go without food, over-exercise, or purge?

- Do you base your self-worth on your weight or body size?

Believe it or not, anorexia isn’t really about food and weight—at least not at its core. Eating disorders are much more complicated than that. The food and weight-related issues are symptoms of something deeper: things like depression, loneliness, insecurity, pressure to be perfect, or feeling out of control. Things that no amount of dieting or weight loss can cure.

What need does anorexia meet in your life?

It’s important to understand that anorexia meets a need in your life. For example, you may feel powerless in many parts of your life, but you can control what you eat. Saying “no” to food, getting the best of hunger, and controlling the number on the scale may make you feel strong and successful—at least for a short while. You may even come to enjoy your hunger pangs as reminders of a “special talent” that most people can’t achieve.

Anorexia may also be a way of distracting yourself from difficult emotions. When you spend most of your time thinking about food, dieting, and weight loss, you don’t have to face other problems in your life or deal with complicated emotions.

Unfortunately, any boost you get from starving yourself or shedding pounds is extremely short-lived. Dieting and weight loss can’t repair the negative self-image at the heart of anorexia. The only way to do that is to identify the emotional need that self-starvation fulfills and find other ways to meet it.

| The difference between dieting and anorexia | |

| Healthy Dieting | Anorexia |

|

Healthy dieting is an attempt to control weight. |

Anorexia is an attempt to control your life and emotions. |

|

Your self-esteem is based on more than just weight and body image. |

Your self-esteem is based entirely on how much you weigh and how thin you are. |

|

You view weight loss as a way to improve your health and appearance. |

You view weight loss as a way to achieve happiness. |

|

Your goal is to lose weight in a healthy way. |

Becoming thin is all that matters; health is not a concern. |

Living with anorexia means you’re constantly hiding your habits. This makes it hard at first for friends and family to spot the warning signs. When confronted, you might try to explain away your disordered eating and wave away concerns. But as anorexia progresses, people close to you wont be able to deny their instincts that something is wrong—and neither should you.

As anorexia develops, you become increasingly preoccupied with the number on the scale, how you look in the mirror, and what you can and can’t eat.

Anorexic food behavior signs and symptoms

- Dieting despite being thin – Following a severely restricted diet. Eating only certain low-calorie foods. Banning “bad” foods such as carbohydrates and fats.

- Obsession with calories, fat grams, and nutrition – Reading food labels, measuring and weighing portions, keeping a food diary, reading diet books.

- Pretending to eat or lying about eating – Hiding, playing with, or throwing away food to avoid eating. Making excuses to get out of meals (“I had a huge lunch” or “My stomach isn’t feeling good.”).

- Preoccupation with food – Constantly thinking about food. Cooking for others, collecting recipes, reading food magazines, or making meal plans while eating very little.

- Strange or secretive food rituals – Refusing to eat around others or in public places. Eating in rigid, ritualistic ways (e.g. cutting food “just so”, chewing food and spitting it out, using a specific plate).

Anorexic appearance and body image signs and symptoms

- Dramatic weight loss – Rapid, drastic weight loss with no medical cause.

- Feeling fat, despite being underweight – You may feel overweight in general or just “too fat” in certain places such as the stomach, hips, or thighs.

- Fixation on body image – Obsessed with weight, body shape, or clothing size. Frequent weigh-ins and concern over tiny fluctuations in weight.

- Harshly critical of appearance – Spending a lot of time in front of the mirror checking for flaws. There’s always something to criticize. You’re never thin enough.

- Denial that you’re too thin – You may deny that your low body weight is a problem, while trying to conceal it (drinking a lot of water before being weighed, wearing baggy or oversized clothes).

Purging signs and symptoms

- Using diet pills, laxatives, or diuretics – Abusing water pills, herbal appetite suppressants, prescription stimulants, ipecac syrup, and other drugs for weight loss.

- Throwing up after eating – Frequently disappearing after meals or going to the bathroom. May run the water to disguise sounds of vomiting or reappear smelling like mouthwash or mints.

- Compulsive exercising – Following a punishing exercise regimen aimed at burning calories. Exercising through injuries, illness, and bad weather. Working out extra hard after bingeing or eating something “bad.”

There are no simple answers to the causes of anorexia and other eating disorders. Anorexia is a complex condition that arises from a combination of many social, emotional, and biological factors. Although our culture’s idealization of thinness plays a powerful role, there are many other contributing factors, including your family environment, emotional difficulties, low self-esteem, and traumatic experiences you may have gone through in the past.

Psychological causes and risk factors for anorexia

People with anorexia are often perfectionists and overachievers. They’re the “good” daughters and sons who do what they’re told, excel in everything they do, and focus on pleasing others. But while they may appear to have it all together, inside they feel helpless, inadequate, and worthless. Through their harshly critical lens, if they’re not perfect, they’re a total failure.

Family and social pressures

In addition to the cultural pressure to be thin, there are other family and social pressures that can contribute to anorexia. This includes participation in an activity that demands slenderness, such as ballet, gymnastics, or modeling. It also includes having parents who are overly controlling, put a lot of emphasis on looks, diet themselves, or criticize their children’s bodies and appearance. Stressful life events—such as the onset of puberty, a breakup, or going away to school—can also trigger anorexia.

Biological causes of anorexia

Research suggests that a genetic predisposition to anorexia may run in families. If a girl has a sibling with anorexia, she is 10 to 20 times more likely than the general population to develop anorexia herself. Brain chemistry also plays a significant role. People with anorexia tend to have high levels of cortisol, the brain hormone most related to stress, and decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine, which are associated with feelings of well-being.

Major risk factors for anorexia nervosa

|

|

One thing is certain about anorexia. Severe calorie restriction has dire physical effects. When your body doesn’t get the fuel it needs to function normally, it goes into starvation mode and slows down to conserve energy. Essentially, your body begins to consume itself. If self-starvation continues and more body fat is lost, medical complications pile up and your body and mind pay the price.

Some of the physical effects of anorexia include:

|

|

Deciding to get help for anorexia is not an easy choice to make. It’s not uncommon to feel like anorexia is part of your identity—or even your “friend.”

You may think that anorexia has such a powerful hold over you that you’ll never be able to overcome it. But while change is hard, it is possible.

Steps to anorexia recovery

- Admit you have a problem. Up until now, you’ve been invested in the idea that life will be better—that you’ll finally feel good—if you lose more weight. The first step in anorexia recovery is admitting that your relentless pursuit of thinness is out of your control and acknowledging the physical and emotional damage that you’ve suffered because of it.

- Talk to someone. It can be hard to talk about what you’re going through, especially if you’ve kept your anorexia a secret for a long time. You may be ashamed, ambivalent, or afraid. But it’s important to understand that you’re not alone. Find a good listener—someone who will support you as you try to get better.

- Stay away from people, places, and activities that trigger your obsession with being thin. You may need to avoid looking at fashion or fitness magazines, spend less time with friends who constantly diet and talk about losing weight, and stay away from weight loss web sites and “pro-ana” sites that promote anorexia.

- Seek professional help. The advice and support of trained eating disorder professionals can help you regain your health, learn to eat normally again, and develop healthier attitudes about food and your body.

Overcoming anorexia

It may seem like there’s no escape from your eating disorder, but recovery is within your reach. With treatment, support from others, and smart self-help strategies, you can overcome bulimia and gain true self-confidence. Read Eating Disorder Treatment and Recovery.

Since anorexia involves both mind and body, a team approach to treatment is often best. Those who may be involved in anorexia treatment include medical doctors, psychologists, counselors, and dieticians. The participation and support of family members also makes a big difference in treatment success. Having a team around you that you can trust and rely on will make recovery easier.

Treating anorexia involves three steps:

- Getting back to a healthy weight

- Starting to eat more food

- Changing how you think about yourself and food

Medical treatment for anorexia

The first priority in anorexia treatment is addressing and stabilizing any serious health issues. Hospitalization may be necessary if you are dangerously malnourished or so distressed that you no longer want to live. You may also need to be hospitalized until you reach a less critical weight. Outpatient treatment is an option when you’re not in immediate medical danger.

Nutritional treatment for anorexia

A second component of anorexia treatment is nutritional counseling. A nutritionist or dietician will teach you about healthy eating and proper nutrition. The nutritionist will also help you develop and follow meal plans that include enough calories to reach or maintain a normal, healthy weight.

Counseling and therapy for anorexia

Counseling is crucial to anorexia treatment. Its goal is to identify the negative thoughts and feelings that fuel your eating disorder and replace them with healthier, less distorted beliefs. Another important goal of counseling is to teach you how to deal with difficult emotions, relationship problems, and stress in a productive, rather than a self-destructive, way.

Getting past your fear of gaining weight

Getting back to a normal weight is no easy task. The thought of gaining weight is probably extremely frightening—especially if you’re being forced—and you may be tempted to resist. But research shows that the closer your body weight is to normal at the end of treatment, the greater your chance of recovery, so getting to a healthy weight should be a top treatment goal.

Try to understand that your fear of gaining weight is a symptom of your anorexia. Reading about anorexia or talking to other people who have lived with it can help. It also helps to be honest about your feelings and fears—including your family and your treatment team. The better they understand what you’re going through, the better support you’ll receive.

Encouraging an anorexic friend or family member to get treatment is the most caring and supportive thing you can do. But because of the defensiveness and denial involved in anorexia, you’ll need to tread lightly. Waving around articles about the dire effects of anorexia or declaring “You’ll die if you don’t eat!” probably won’t work. A better approach is to gently express your concerns and let the person know that you’re available to listen. If your loved one is willing to talk, listen without judgment, no matter how out of touch the person sounds.

It’s deeply distressing to know that your child or someone you love may be struggling with anorexia. There’s no way to solve the problem yourself, but here are a few ideas for what you can do now to help make a difference for someone you love.

Tips for helping a person with anorexia

- Think of yourself as an “outsider.” In other words, someone not suffering from anorexia. In this position, there isn’t a lot you can do to “solve” your loved one’s anorexia. It is ultimately the individual’s choice to decide when they are ready.

- Be a role model for healthy eating, exercising, and body image. Don’t make negative comments about your own body or anyone else’s.

- Take care of yourself. Seek advice from a health professional, even if your friend or family member won’t. And you can bring others—from peers to parents—into the circle of support.

- Don’t act like the food police. A person with anorexia needs compassion and support, not an authority figure standing over the table with a calorie counter.

- Avoid threats, scare tactics, angry outbursts, and put-downs. Bear in mind that anorexia is often a symptom of extreme emotional distress and develops out of an attempt to manage emotional pain, stress, and/or self-hate. Negative communication will only make it worse

What is bulimia?

Bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by frequent episodes of binge eating, followed by frantic efforts to avoid gaining weight.

When you’re struggling with bulimia, life is a constant battle between the desire to lose weight or stay thin and the overwhelming compulsion to binge eat.

You don’t want to binge—you know you’ll feel guilty and ashamed afterwards—but time and again you give in. During an average binge, you may consume from 3,000 to 5,000 calories in one short hour.

After it ends, panic sets in and you turn to drastic measures to “undo” the binge, such as taking ex-lax, inducing vomiting, or going for a ten-mile run. And all the while, you feel increasingly out of control.

It’s important to note that bulimia doesn’t necessarily involve purging—physically eliminating the food from your body by throwing up or using laxatives, enemas, or diuretics. If you make up for your binges by fasting, exercising to excess, or going on crash diets, this also qualifies as bulimia.

SIGNS, SYMPTOMS, TREATMENT, AND HELP

We’ve all been there: turning to food when feeling lonely, bored, or stressed. But with bulimia, overeating is more like a compulsion. And instead of eating sensibly to make up for it, you punish yourself by purging, fasting, or exercising to get rid of the calories. This vicious cycle of binging and purging takes a toll on your body and emotional well-being. But the cycle can be broken. Treatment can help you develop a healthier relationship with food and overcome feelings of anxiety, guilt, and shame.

Am I Bulimic?

Ask yourself the following questions. The more “yes” answers, the more likely you are suffering from bulimia or another eating disorder.

- Are you obsessed with your body and your weight?

- Does food and dieting dominate your life?

- Are you afraid that when you start eating, you won’t be able to stop?

- Do you ever eat until you feel sick?

- Do you feel guilty, ashamed, or depressed after you eat?

- Do you vomit or take laxatives to control your weight?

Amy’s Story

Once again, Amy is on a liquid diet. “I’m going to stick with it,” she tells herself. “I won’t give in to the cravings this time.” But as the day goes on, Amy’s willpower weakens. All she can think about is food. Finally, she decides to give in to the urge to binge. She can’t control herself any longer. She grabs a pint of ice cream out of the freezer, inhaling it within a matter of minutes. Then it’s on to anything else she can find in the kitchen. After 45 minutes of bingeing, Amy is so stuffed that her stomach feels like it’s going to burst. She’s disgusted with herself and terrified by the thousands of calories she’s consumed. She runs to the bathroom to throw up. Afterwards, she steps on the scale to make sure she hasn’t gained any weight. She vows to start her diet again tomorrow. Tomorrow, it will be different.

The binge and purge cycle

Dieting triggers bulimia’s destructive cycle of binging and purging. The irony is that the more strict and rigid the diet, the more likely it is that you’ll become preoccupied, even obsessed, with food. When you starve yourself, your body responds with powerful cravings—its way of asking for needed nutrition.

As the tension, hunger, and feelings of deprivation build, the compulsion to eat becomes too powerful to resist: a “forbidden” food is eaten; a dietary rule is broken. With an all-or-nothing mindset, you feel any diet slip-up is a total failure. After having a bite of ice cream, you might think, “I’ve already blown It, so I might as well go all out.”

Unfortunately, the relief that binging brings is extremely short-lived. Soon after, guilt and self-loathing set in. And so you purge to make up for binging and regain control.

Unfortunately, purging only reinforces binge eating. Though you may tell yourself, as you launch into a new diet, that this is the last time, in the back of your mind there’s a voice telling you that you can always throw up or use laxatives if you lose control again. What you may not realize is that purging doesn’t come close to wiping the slate clean after a binge.

Purging does NOT prevent weight gain

Purging isn’t effective at getting rid of calories, which is why most people suffering with bulimia end up gaining weight over time. Vomiting immediately after eating will only eliminate 50% of the calories consumed at best—and usually much less. This is because calorie absorption begins the moment you put food in the mouth. Laxatives and diuretics are even less effective. Laxatives get rid of only 10% of the calories eaten, and diuretics do nothing at all. You may weigh less after taking them, but that lower number on the scale is due to water loss, not true weight loss.

Signs and symptoms of bulimia

If you’ve been living with bulimia for a while, you’ve probably “done it all” to conceal your binging and purging habits. It’s only human to feel ashamed about having a hard time controlling yourself with food, so you most likely binge alone. If you eat a box of doughnuts, then you’ll replace them so your friends or family won’t notice. When buying food for a binge, you might shop at four separate markets so the checker won’t guess. But despite your secret life, those closest to you probably have a sense that something is not right.

Binge eating signs and symptoms

- Lack of control over eating – Inability to stop eating. Eating until the point of physical discomfort and pain.

- Secrecy surrounding eating – Going to the kitchen after everyone else has gone to bed. Going out alone on unexpected food runs. Wanting to eat in privacy.

- Eating unusually large amounts of food with no obvious change in weight.

- Disappearance of food, numerous empty wrappers or food containers in the garbage, or hidden stashes of junk food.

- Alternating between overeating and fasting – Rarely eats normal meals. It’s all-or-nothing when it comes to food.

Purging signs and symptoms

- Going to the bathroom after meals – Frequently disappears after meals or takes a trip to the bathroom to throw up. May run the water to disguise sounds of vomiting.

- Using laxatives, diuretics, or enemas after eating. May also take diet pills to curb appetite or use the sauna to “sweat out” water weight.

- Smell of vomit – The bathroom or the person may smell like vomit. They may try to cover up the smell with mouthwash, perfume, air freshener, gum, or mints.

- Excessive exercising – Works out strenuously, especially after eating. Typical activities include high-intensity calorie burners such as running or aerobics.

Physical signs and symptoms of bulimia

- Calluses or scars on the knuckles or hands from sticking fingers down the throat to induce vomiting.

- Puffy “chipmunk” cheeks caused by repeated vomiting.

- Discolored teeth from exposure to stomach acid when throwing up. May look yellow, ragged, or clear.

- Not underweight – Men and women with bulimia are usually normal weight or slightly overweight. Being underweight while purging might indicate a purging type of anorexia.

- Frequent fluctuations in weight – Weight may fluctuate by 10 pounds or more due to alternating episodes of bingeing and purging.

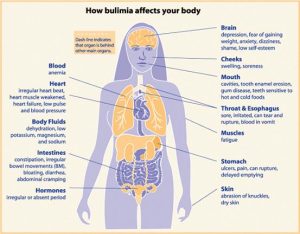

Effects of bulimia

When you are living with bulimia, you are putting your body—and even your life—at risk. The most dangerous side effect of bulimia is dehydration due to purging. Vomiting, laxatives, and diuretics can cause electrolyte imbalances in the body, most commonly in the form of low potassium levels. Low potassium levels trigger a wide range of symptoms ranging from lethargy and cloudy thinking to irregular heartbeat and death. Chronically low levels of potassium can also result in kidney failure.

Other common medical complications and adverse effects of bulimia include:

|

|

The dangers of ipecac syrup

If you use ipecac syrup, a medicine used to induce vomiting, after a binge, take caution. Regular use of ipecac syrup can be deadly. Ipecac builds up in the body over time. Eventually it can lead to heart damage and sudden cardiac arrest, as it did in the case of singer Karen Carpenter.

Source: National Women’s Health Information Center

Bulimia causes and risk factors

There is no single cause of bulimia. While low self-esteem and concerns about weight and body image play major roles, there are many other contributing causes. In most cases, people suffering with bulimia—and eating disorders in general—have trouble managing emotions in a healthy way. Eating can be an emotional release so it’s not surprising that people binge and purge when feeling angry, depressed, stressed, or anxious.

One thing is certain. Bulimia is a complex emotional issue. Major causes and risk factors for bulimia include:

- Poor body image: Our culture’s emphasis on thinness and beauty can lead to body dissatisfaction, particularly in young women bombarded with media images of an unrealistic physical ideal.

- Low self-esteem: People who think of themselves as useless, worthless, and unattractive are at risk for bulimia. Things that can contribute to low self-esteem include depression, perfectionism, childhood abuse, and a critical home environment.

- History of trauma or abuse: Women with bulimia appear to have a higher incidence of sexual abuse. People with bulimia are also more likely than average to have parents with a substance abuse problem or psychological disorder.

- Major life changes: Bulimia is often triggered by stressful changes or transitions, such as the physical changes of puberty, going away to college, or the breakup of a relationship. Binging and purging may be a negative way to cope with the stress.

- Appearance-oriented professions or activities: People who face tremendous image pressure are vulnerable to developing bulimia. Those at risk include ballet dancers, models, gymnasts, wrestlers, runners, and actors.

Getting help for bulimia

If you are living with bulimia, you know how scary it feels to be so out of control. Knowing that you are harming your body just adds to the fear. But take heart: change is possible. Regardless of how long you’ve struggled with bulimia, you can learn to break the binge and purge cycle and develop a healthier attitude toward food and your body.

Taking steps toward recovery is tough. It’s common to feel ambivalent about giving up your binging and purging, even though it’s harmful. If you are even thinking of getting help for bulimia, you are taking a big step forward.

Steps to bulimia recovery

If you or a loved one has

bulimia…

Call

the National Eating Disorders Association’s toll-free hotline at for

free referrals, information, and advice.

- Admit you have a problem. Up until now, you’ve been invested in the idea that life will be

better—that you’ll finally feel good—if you lose more weight and control what you eat. The first step in bulimia

recovery is admitting that your relationship to food is distorted and out of control. - Talk to someone. It can be hard to talk about what you’re going through, especially if you’ve

kept your bulimia a secret for a long time. You may be ashamed, ambivalent, or afraid of what others will think.

But it’s important to understand that you’re not alone. Find a good listener—someone who will support you as you

try to get better. - Stay away from people, places, and activities that trigger the temptation to binge or purge.

You may need to avoid looking at fashion or fitness magazines, spend less time with friends who constantly diet

and talk about losing weight, and stay away from weight loss web sites and “pro-mia” sites that promote bulimia.

You may also need to be careful when it comes to meal planning and cooking magazines and shows. - Seek professional help. The advice and support of trained eating disorder professionals can

help you regain your health, learn to eat normally again, and develop healthier attitudes about food and your

body.

The importance of deciding not to diet

Treatment for bulimia is much more likely to succeed when you stop dieting. Once you stop trying to restrict calories and follow strict dietary rules, you will no longer be overwhelmed with cravings and thoughts of foods. By eating normally, you can break the binge-and-purge cycle and still reach a healthy, attractive weight.

Bulimia treatment and therapy

To stop the cycle of bingeing and purging, it’s important to seek professional help early, follow through with treatment, and resolve the underlying emotional issues that caused the bulimia in the first place.

Therapy for bulimia

Because poor body image and low self-esteem lie at the heart of bulimia, therapy is an important part of recovery. It’s common to feel isolated and shamed by your bingeing and purging, and therapists can help with these feelings.

The treatment of choice for bulimia is cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy targets the unhealthy eating behaviors of bulimia and the unrealistic, negative thoughts that fuel them. Here’s what to expect in bulimia therapy:

- Breaking the binge-and-purge cycle – The first phase of bulimia treatment focuses on stopping the vicious cycle of bingeing and purging and restoring normal eating patterns. You learn to monitor your eating habits, avoid situations that trigger binges, cope with stress in ways that don’t involve food, eat regularly to reduce food cravings, and fight the urge to purge.

- Changing unhealthy thoughts and patterns – The second phase of bulimia treatment focuses on identifying and changing dysfunctional beliefs about weight, dieting, and body shape. You explore attitudes about eating, and rethink the idea that self-worth is based on weight.

- Solving emotional issues – The final phase of bulimia treatment involves targeting emotional issues that caused the eating disorder in the first place. Therapy may focus on relationship issues, underlying anxiety and depression, low self-esteem, and feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Overcoming bulimia

It may seem like there’s no escape from your eating disorder, but recovery is within your reach. With treatment, support from others, and smart self-help strategies, you can overcome bulimia and gain true self-confidence. Read: Eating Disorder Treatment and Recovery.

Helping a person with bulimia

If you suspect that your friend or family member has bulimia, talk to the person about your concerns. Your loved one may deny bingeing and purging, but there’s a chance that he or she will welcome the opportunity to open up about the struggle. Either way, bulimia should never be ignored. The person’s physical and emotional health is at stake.

It’s painful to know your child or someone you love may be binging and purging. You can’t force a person with an eating disorder to change and you can’t do the work of recovery for your loved one. But you can help by offering your compassion, encouragement, and support throughout the treatment process.

If your loved one has bulimia

- Offer compassion and support. Keep in mind that the person may get defensive or angry. But if he or she does open up, listen without judgment and make sure the person knows you care.

- Avoid insults, scare tactics, guilt trips, and patronizing comments. Since bulimia is often a caused and exacerbated by stress, low self-esteem, and shame, negativity will only make it worse.

- Set a good example for healthy eating, exercising, and body image. Don’t make negative comments about your own body or anyone else’s.

- Accept your limits. As a parent or friend, there isn’t a lot you can do to “fix” your loved one’s bulimia. The person with bulimia must make the decision to move forward.

- Take care of yourself. Know when to seek advice for yourself from a counselor or health professional. Dealing with an eating disorder is stressful, and it will help if you have your own support system in place.

To schedule an appointment for an initial appointment, please call (702) 240-8639. Our administrative team is ready to answer your phone call Monday-Friday 8:00am-5:00pm. If we are busy assisting other clients or away from our desk, we ask that you leave a message, and we will return your phone call within two business days. You may also reach us via email.

Your first appointment will be with a mental health provider. If you are a child or adolescent, your parent or guardian will be with you during this appointment. During this initial visit, your provider will explain the expectations of treatment and ask questions to get to know you. Your provider will also initiate an extensive Biopsychosocial Diagnostic Interview asking questions about your presenting problems, current living situation, family history, relationship history, medical history, academic/employment history, nutrition, lifestyle, and other pertinent information. This allows your provider to properly diagnose the issues, assess your current needs, and work with you to build an individualized treatment plan for future sessions.

Foundations Counseling Center is in-network with most insurances. Most policies include mental health benefits and pay for services, as long as treatment meets medical necessity. Others cover only a limited amount of sessions. Some insurance policies pay for 100% of the services. Others apply co-pays, co-insurances, and deductibles for services, leaving you financially responsible to pay a portion. Most insurance companies cover all mental health conditions. Others exclude certain diagnoses and certain outpatient services. It is best if you contact your insurance company to learn and understand the benefit details of your insurance coverage.